I’m excited to share an interview with two researchers that I’ve had the privilege of collaborating with on a recently released paper studying how open source maintainers adjust their work after they start using GitHub Copilot:

- Manuel Hoffmann is a postdoctoral scholar at the Laboratory for Innovation Science at Harvard housed within the Digital, Data, and Design Institute at Harvard Business School. He is also affiliated with Stanford University. His research interests lie in social and behavioral aspects around open source software and artificial intelligence, under the broader theme of innovation and technology management, with the aim of better understanding strategic aspects for large, medium-sized, and entrepreneurial firms.

- Sam Boysel is a postdoctoral fellow at the Laboratory for Innovation Science at Harvard. He is an applied microeconomist with research interests at the intersection of digital economics, labor and productivity, industrial organization, and socio-technical networks. Specifically, his work has centered around the private provision of public goods, productivity in open collaboration, and welfare effects within the context of open source software (OSS) ecosystems.

Research Q&A

Kevin: Thanks so much for chatting, Manuel and Sam! So, it seems like the paper’s really making the rounds. Could you give a quick high-level summary for our readers here?

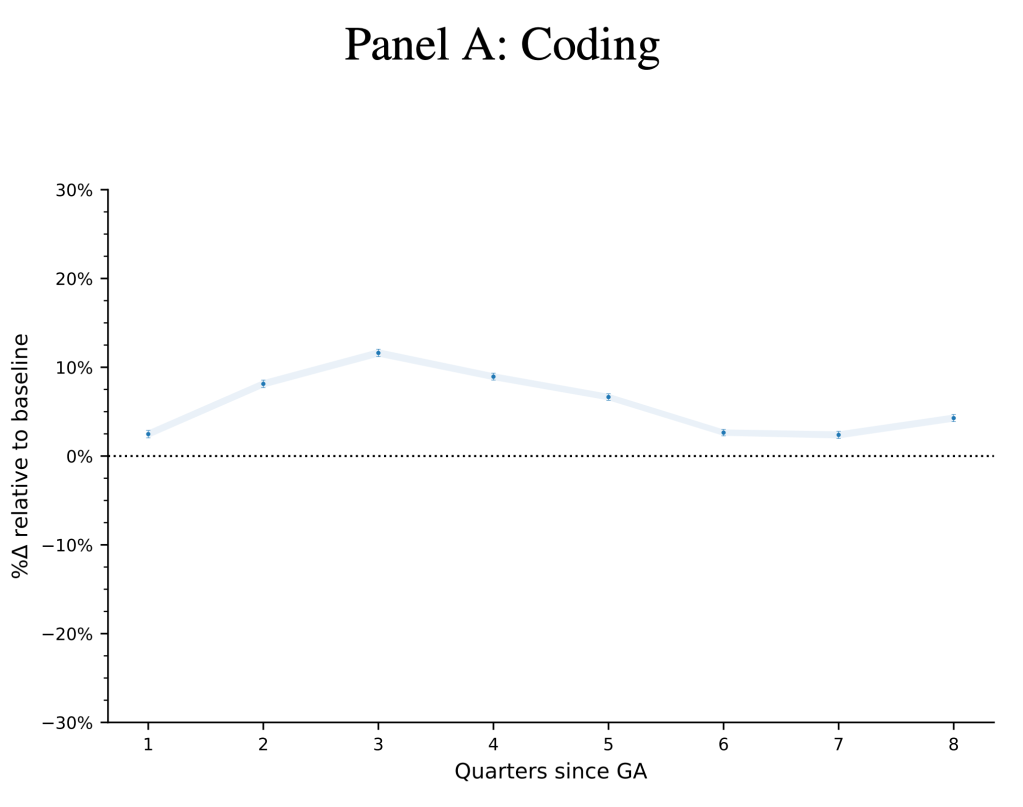

Manuel: Thanks to the great collaboration with you, Sida Peng from Microsoft and Frank Nagle from Harvard Business School, we study the impact of GitHub Copilot on developers and how this generative AI alters the nature of work. We find that when you provide developers in the context of open source software with a generative AI tool that reduces the cost of the core work of coding, developers increase their coding activities and reduce their project management activities. We find our results are strongest in the first year after the introduction but still exist even two years later. The results are driven by developers who are working more autonomously and less collaboratively since they do not have to engage with other humans to solve a problem but they can solve the problem through AI assistance.

Sam: That’s exactly right. We tried to even further understand the nature of work by digging into the paradigm of exploration vs exploitation. Loosely speaking, exploitation is the idea to exert effort towards the most lucrative of the already known options while exploration implies to experiment to find new options with a higher potential return. We tested this idea in the context of GitHub. Developers that had access to GitHub Copilot are engaged in more experimentation and less exploitation, that is, they start new projects with access to AI and have a lower propensity to work on older projects. Additionally, they expose themselves to more languages that they were previously not exposed to and in particular to languages that are valued higher in the labor market. A back-of-the-envelope calculation from purely experimentation among new languages due to GitHub Copilot suggests a value of around half a billion USD within a year.

Kevin: Interesting! Could you provide an overview of the methods you used in your analysis?

Manuel: Would be happy to! We are using a regression discontinuity design in this work, which is as close as you can get to a randomized control trial when purely using pre-existing data, such as the one from GitHub, without introducing randomization by the researcher. Instead, the regression discontinuity design is based on a ranking of developers and a threshold that GitHub uses to determine eligibility for free access to GitHub Copilot’s top maintainer program.

Sam: The main idea of this method is that a developer that is right below the threshold is roughly identical to a developer that is right above the threshold. Stated differently, by chance a developer happened to have a ranking that made them eligible for the generative AI while they could as well not have been eligible. Taken together with the idea that developers neither know the threshold nor the internal ranking from GitHub, we can be certain that the changes that we observe in coding, project management, and the other activities on the platform are only driven by the developers having access to GitHub Copilot and nothing else.

Kevin: Nice! Follow-up question: could you provide an “explain like I’m 5” overview of the methods you used in your analysis?

Manuel: Sure thing, let’s illustrate the problem a bit more. Some people use GitHub Copilot and others don’t. If we just looked at the differences between people who use GitHub Copilot vs. those who don’t, we’d be able to see that certain behaviors and characteristics are associated with GitHub Copilot usage. For example, we might find that people who use GitHub Copilot push more code than those who don’t. Crucially, though, that would be a statement about correlation and not about causation. Often, we want to figure out whether X causes Y, and not just that X is correlated with Y. Going back to the example, if it’s the case that those who use GitHub Copilot push more code than those who don’t, these are a few of the different explanations that might be at play:

- Using GitHub Copilot causes people to push more code.

- Pushing more code causes people to use GitHub Copilot.

- There’s something else that both causes people to use GitHub Copilot and causes them to push more code (for example, being a professional developer).

Because (1), (2), and (3) could each result in data showing a correlation between GitHub Copilot usage and code pushes, just finding a correlation isn’t super interesting. One way you could isolate the cause and effect relationship between GitHub Copilot and code pushes, though, is through a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

In an RCT, we randomly assign people to use GitHub Copilot (the treatment group), while others are forbidden from using GitHub Copilot (the control group). As long as the assignment process is truly random and the users comply with their assignments, any outcome differences between the treatment and control groups can be attributed to GitHub Copilot usage. In other words, you could say that GitHub Copilot caused those effects. However, as anyone in the healthcare field can tell you, large-scale RCTs over long-time periods are often prohibitively expensive, as you’d need to recruit subjects to participate, monitor them to see if they complied with their assignments, and follow up with them over time.

Sam: That’s right. So, instead, wouldn’t it be great if there would be a way to observe developers without running an RCT and still draw valid causal conclusions about GitHub Copilot usage? That’s where the regression discontinuity design (RDD) comes in. The random assignment aspect of an RCT allows us to compare the outcomes of two virtually identical groups. Sometimes, however, randomness already exists in a system, which we can use as a natural experiment. In the case of our paper, this randomness came in the form of GitHub’s internal ranking for determining which open source maintainers were eligible for free access to GitHub Copilot.

Let’s walk through a simplified example. Let’s imagine that there were one million repositories that were ranked on some set of metrics and the rule was that the top 500,000 repositories are eligible for free access to GitHub Copilot. If we compared the #1 ranked repository with the #1,000,000 ranked repository, then we would probably find that those two are quite different from each other. After all, the #1 repository is the best repository on GitHub by this metric while the #1,000,000 repository is a whole 999,999 rankings away from it. There are probably meaningful differences in code quality, documentation quality, project purpose, maintainer quality, etc. between the two repositories, so we would not be able to say that the only reason why there was a difference in outcomes for the maintainers of repository #1 vs. repository #1,000,000 was because of free access to GitHub Copilot.

However, what about repository #499,999 vs. repository #500,001? Those repositories are probably very similar to each other, and it was all down to random chance as to which repository made it over the eligibility threshold and which one did not. As a result, there is a strong argument that any differences in outcomes between those two repositories is solely due to repository #499,999 having free access to GitHub Copilot and repo #500,001 not having free access. Practically, you’ll want to have a larger sample size than just two, so you would compare a narrow set of repositories just above and below the eligibility threshold against each other.

Kevin: Thanks, that’s super helpful. I’d be curious about the limitations of your paper and data that you wished you had for further work. What would the ideal dataset(s) look like for you?

Manuel: Fantastic question! Certainly, no study is perfect and there will be limitations. We are excited to better understand generative AI and how it affects work in the future. As such, one limitation is the availability of information from private repositories. We believe that if we were to have information on private repositories we could test whether there is some more experimentation going on in private projects and that project improvements that were done with generative AI in private may spill over to the public to some degree over time.

Sam: Another limitation of our study is the language-based exercise to provide a value of GitHub Copilot. We show that developers focus on higher value languages that they did not know previously and we extrapolated this estimate to all top developers. However, this estimate is certainly only a partial equilibrium value since developer wages may change over time in a full equilibrium situation if more individuals offer their services for a given language. However, despite the limitation, the value seems to be an underestimate since it does not contain any non-language specific experimentation value and non-experimentation value that is derived from GitHub Copilot.

Kevin: Predictions for the future? Recommendations for policymakers? Recommendations for developers?

Manuel: One simple prediction for the future is that AI incentivizes the activity for which it lowers the cost. However, it is not clear yet which parts will be incentivized through AI tools since they can be applied to many domains. It is likely that there are going to be a multitude of AI tools that incentivize different work activities which will eventually lead to employees, managers at firms, and policy-makers having to consider on which activity they want to put weight. We also would have to think about new recombinations of work activities. Those are difficult to predict. Avi Goldfarb, a prolific professor from the University of Toronto, gave an example of the steam engine with his colleagues. Namely, work was organized in the past around the steam engine as a power source but once electric motors were invented, that was not necessary anymore and structural changes happened. Instead of arranging all of the machinery around a giant steam engine in the center of the factory floor, electricity enabled people to design better arrangements, which led to boosts in productivity. I find this historical narrative quite compelling and can imagine similarly for AI that the greatest power still remains to be unlocked and that it will be unlocked once we know how work processes can be re-organized. Developers can think as well about how their work may change in the future. Importantly, developers can actively shape that future since they are closest to the development of machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence technologies.

Sam: Adding on to those points, it is not clear when work processes change and whether it will have an inequality reducing or enhancing effect. Many predictions point towards an inequality enhancing effect since the training of large-language models requires substantial computing power which is often only in the hands of a few players. On the other hand, it has been documented that especially lower ability individuals seem to benefit the most from generative AI, at least in the short-term. As such, it’s imperative to understand how the benefits of generative AI are distributed across society. If not, are there equitable, welfare-improving interventions that can correct these imbalances? An encouraging result of our study suggests that generative AI can be especially impactful for relatively lesser skilled workers:

for more information with summary statistics of each proxy.](https://github.blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/coding_by_ability.png?w=1024&resize=2300%2C1126)

for more information with summary statistics of each proxy.](https://github.blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/project_management_by_ability.png?w=1024&resize=2316%2C1082)

Sam (continued): Counter to widespread speculation that generative AI will replace many entry level tasks, we find reason to believe that AI can also lower the costs of experimentation and exploration, reduce barriers to entry, and level the playing field in certain segments of the labor market. It would be prudent for policymakers to monitor distributional effects of generative AI, allowing the new technology to deliver equitable benefits where it does so naturally but at the same time intervening in cases where it falls short.

Personal Q&A

Kevin: I’d like to change gears a bit to chat more about your personal stories. Manuel, I know you’ve worked on research analyzing health outcomes with Stanford, diversity in TV stations, and now you’re studying nerds on the internet. Would love to learn about your journey to getting there.

Manuel: Sure! I was actually involved with “nerds on the internet” longer than my vita might suggest. Prior to my studies, I was using open source software, including Linux and Ubuntu, and programming was a hobby for me. I enjoyed the freedom that one had on the personal computer and the internet. During my studies, I discovered economics and business studies as a field of particular interest. Since I was interested in causal inference and welfare from a broader perspective, I learned how to use experimental and quasi-experimental studies to better understand social, medical and technological innovation that are relevant for individuals, businesses, and policy makers. I focused on labor and health during my PhD and afterwards I was able to lean a bit more into health at Stanford University. During my time at Harvard Business School, the pendulum swung back a bit towards labor. As such, I was in the fortunate position—thanks to the study of the exciting field of open source software—to continuously better understand both spaces.

Kevin: Haha, great to hear your interest in open source runs deep! Sam, you also have quite the varied background, analyzing cleantech market conditions and the effects of employment verification policies, and you also seem to have been studying nerds on the internet for the past several years. Could you share a bit about your path?

Sam: I’ve been a computing and open source enthusiast since I got my hands on a copy of “OpenSUSE for Dummies” in middle school. As an undergraduate, I was drawn to the social science aspect of economics and its ability to explain or predict human behavior across a wide range of settings. After bouncing around a number of subfields in graduate school, I got the crazy idea to combine my field of study with my passion and never looked back. Open source is an incredibly data-rich environment with a wealth of research questions interesting to economists. I’ve studied the role of peer effects in driving contribution, modelled the formation of software dependency networks using strategic behavior and risk aversion, and explored how labor market competition shapes open source output.

And thanks, Kevin. I’ll be sure to work “nerds on the internet” into the title of the next paper.

Kevin: Finding a niche that you’re passionate about is such a joy, and I’m curious about how you’ve found living in that niche. What’s the day-to-day like for you both?

Manuel: The day-to-day can vary but as an academic, there are a few tasks that are recurring at a big picture level. Research, teaching and other work. Let’s focus on the research bucket. I am quite busy with working on causal inference papers, refining them but also speaking to audiences to communicate our work. Some of the work is done jointly, some by oneself, so there is a lot of variation, and the great part of being an academic is that one can choose that variation oneself through the projects one selects. Over time one has to juggle many balls. Hence, I am working on finishing prior papers in the space of health; for example, some that you alluded to previously on Television, Health and Happiness and Vaccination at Work, but also in the space of open source software, importantly, to improve the paper on Generative AI and the Nature of Work. We have continuously more ideas to better understand the world we are living and going to live in at the intersection of open source software and generative AI and, as such, it is very valuable to relate to the literature and eventually answer exciting questions around the future of work with real world data. GitHub is a great resource for that.

Sam: As an applied researcher, I use data to answer questions. The questions can come from current events, from conversations with both friends and colleagues, or simply musing on the intricacies of the open source space. Oftentimes the data comes from publicly observed behavior of firms and individuals recorded on the internet. For example, I’ve used static code analysis and version control history to characterize the development of open source codebases over time. I’ve used job postings data to measure firm demand for open source skills. I’ve used the dependency graphs of packaging ecosystems to track the relationships between projects. I can then use my training in economic theory, econometric methodology, and causal inference to rigorously explore the question. The end result is written up in an article, presented to peers, and iteratively improved from feedback.

Kevin: Have things changed since generative AI tooling came along? Have you found generative AI tools to be helpful?

Manuel: Definitely. I use GitHub Copilot when developing experiments and programming in Javascript together with another good colleague, Daniel Stephenson from Virginia Commonwealth University. It is interesting to observe how often Copilot actually makes code suggestions based on context that are correct. As such, it is an incredibly helpful tool. However, the big picture of what our needs are can only be determined by us, as such, in my experience Copilot does seem to speed up the process and leads to avoiding some mistakes conditional on not just blindly following the AI.

Sam: I’ve only recently begun using GitHub Copilot, but it’s had quite an impact on my workflow. Most social sciences researchers are not skilled software engineers. However, they must also write code to hit deadlines. Before generative AI, the delay between problem and solution was usually characterized by many search queries, parsing Q&A forums or documentation, and a significant time cost. Being able to resolve uncertainty within the IDE is incredible for productivity.

Kevin: Advice you might have for folks who are starting out in software engineering or research? What tips might you give to a younger version of yourself, say, from 10 years ago?

Manuel: I will talk a bit at a higher level. Find work, questions or problems that you deeply care about. I would say that is a universal rule to be satisfied, be it in software engineering, research or in any other area. In a way, think about the motto, “You only live once,” as a pretty applicable misnomer. Another universal advice that has high relevance is to not care too much about the things you cannot change but focus on what you can control. Finally, think about getting advice from many different people, then pick and choose. People have different mindsets and ideas. As such, that can be quite helpful.

Sam:

- Being able to effectively communicate with both groups (software eng and research) is extremely important.

- You’ll do your best work on things you’re truly passionate about.

- Premature optimization truly is the root of all evil.

Kevin: Learning resources you might recommend to someone interested in learning more about this space?

Manuel: There are several aspects we have touched upon—Generative AI Research, Coding with Copilot, Causal Inference and Machine Learning, Economics, and Business Studies. As such, here is one link for each topic that I can recommend:

- Generative AI research: Ethan Mollick’s social media posts

- Coding with Copilot: Advanced GitHub Copilot features

- Causal Inference and Machine Learning: Susan Athey’s Lab

- Economics and Business Studies: NBER Working Papers

I am sure that there are many other great resources out there, many that can also be found on GitHub.

Sam: If you’re interested to get more into how economists and other social scientists think about open source, I highly recommend the following (reasonably entry-level) articles that have helped shape my research approach.

- Lerner, J., & Tirole, J. (2002). Some Simple Economics of Open Source. The Journal of Industrial economics, 50(2), 197-234.

- Bessen, J., & Maskin, E. (2009). Sequential innovation, patents, and imitation. The RAND Journal of Economics, 40(4), 611-635.

- Athey, S., & Ellison, G. (2014). Dynamics of open source movements. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 23(2), 294-316.

For those interested in learning more about the toolkit used by empirical social scientists:

- Cunningham, S. (2021). Causal Inference: The Mixtape. Yale University Press. (website)

(shameless plug) We’ve been putting together a collection of data sources for open source researchers. Contributions welcome!

Kevin: Thank you, Manuel and Sam! We really appreciate you taking the time to share about what you’re working on and your journeys into researching open source.

The post Inside the research: How GitHub Copilot impacts the nature of work for open source maintainers appeared first on The GitHub Blog.

Source: Read MoreÂ