A previous post (Automated testing of Amazon Neptune data access with Apache TinkerPop Gremlin) describes the benefits of unit testing your Apache TinkerPop Gremlin queries and shows how you can add the tests to your CI/CD pipeline. It covered some of the pain points that users would face if they attempted to use Amazon Neptune as the target of their unit testing queries which includes the need to be connected to the internet and the need to connect to the VPC (currently Neptune can only be accessed from within the VPC where it’s hosted). Additionally, you can save money by unit testing with a local Apache TinkerPop Gremlin Server. That post also suggested and demonstrated how you could use TinkerGraph hosted inside a Gremlin Server to address these testing issues.

In this post, I build upon the approach of the previous post and show how you can use TinkerGraph to unit test your transactional workloads. Additionally, I show how to use TinkerGraph in embedded mode. Embedded mode requires the use of Java, but it simplifies the test environment considerably as there is no need to run the server as a separate process.

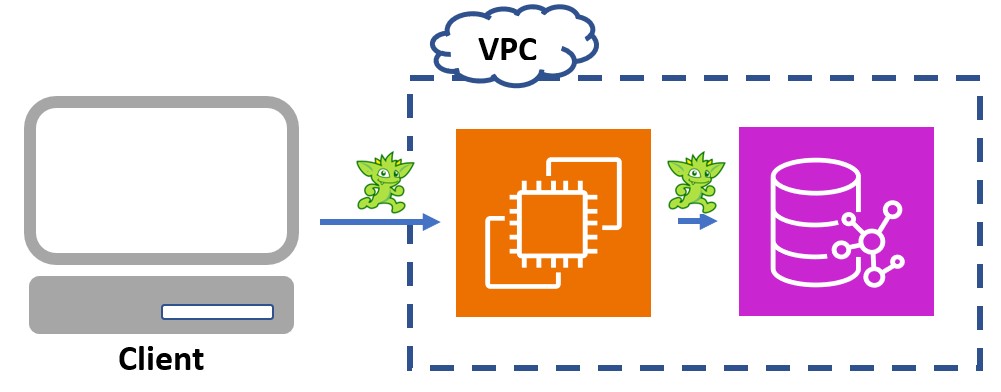

The following two diagrams show the architectural differences between running a query against Neptune and running a query against an embedded graph.

Typical architecture involved in querying Neptune where the query is tunneled through EC2 to Neptune

Architecture involved in querying an embedded graph where the query is executed locally simplifying the environment

The examples in this post assume that you are working with Java and therefore have access to the embedded version of TinkerGraph. See Automated testing of Amazon Neptune data access with Apache TinkerPop Gremlin for more information on how to use the remote version of TinkerGraph inside a Docker container. Note that embedded transactions have more capabilities than remote transactions, so you should only test features that exist for remote transactions (which is what is used when connecting to Neptune).

Overview of Transactions in TinkerGraph and Neptune

Historically, one drawback of using TinkerGraph for testing was that it didn’t support transactions. Transactions are an important part of ensuring correctness when modifying the underlying database, and this type of behavior couldn’t be tested with TinkerGraph. However, with the introduction of the transactional TinkerGraph, TinkerTransactionGraph, in version 3.7.0, this has now changed and TinkerGraph is a suitable solution in most cases.

There are some important differences between the transaction semantics of TinkerTransactionGraph and Neptune and so there are some scenarios that you shouldn’t test with TinkerTransactionGraph. These scenarios should instead be covered by your full testing suite, which should run against Neptune.

First, TinkerTransactionGraph only provides guarantees against dirty reads, so it has a read committed isolation level. Neptune, on the other hand, can provide strong guarantees against dirty reads, phantom reads, and non-repeatable reads. This means that your unit tests should be written with the expectation that only dirty reads can’t occur.

Second, TinkerTransactionGraph employs a form of optimistic locking, so if two transactions attempt to modify the same element, then the second transaction will throw an exception. Neptune uses pessimistic locking (wait-lock approach) and allows for a maximum wait time for acquiring a resource. You may need to account for this optimistic locking behavior by catching TransactionExceptions and retrying.

Additionally, there are differences in Gremlin support between TinkerGraph and Neptune. For more information, see Automated testing of Amazon Neptune data access with Apache TinkerPop Gremlin and Gremlin standards compliance in Amazon Neptune.

TinkerGraph unit testing examples

Let’s walk through an example of a simple airport service.

Prerequisites

To run these examples against the transactional TinkerGraph directly, you must include the tinkergraph-gremlin artifact to your build. For example, if you are using Maven then you would include the following dependency to your pom file:

Version 3.7.0 is used here as an example as it’s the first version that transactional TinkerGraph is available. The version you should use depends on the version of your Neptune engine. See this table for more information.

Alternatively, to run these examples against Neptune, you need access to a Neptune cluster.

Example Airport Service

The following code shows what the interface for such a service might look like:

Now let’s look at what the implementation might look like for the addRoute method. The following code shows the implementation of addRoute and some class fields:

We might want to have two unit tests for this method: one for a non-existent airport, which should fail, and one for valid airports, which should pass. Notice how the instance variable g is used to swap between different graph providers:

Let’s explore what this might look like for a slightly more complicated scenario where you want to temporarily halt routes to a specific airport. The following code illustrates the implementation for a function that stops incoming traffic:

The following code illustrates a unit test for stopIncomingTraffic():

Clean up

If you followed the examples using an embedded TinkerGraph, then it will automatically be cleaned up when the tests end.

If you followed the examples using a Neptune cluster, then you can avoid incurring charges by deleting the Neptune cluster.

Conclusion

Unit testing is an important aspect of CI/CD. For cost and flexibility reasons, you may want to run your unit testing against TinkerGraph. The transactional TinkerGraph, TinkerTransactionGraph, introduced in 3.7.0, is a good candidate when needing to test transactions. For the staging portion of your CI/CD pipeline, which runs less frequent tests like performance or integration, you might consider running against a test instance of Amazon Neptune Serverless, which is a cost-effective way of running spiky test loads and will have the same transaction semantics as your production Neptune database.

“This post is a joint collaboration between Improving and AWS and is being cross-published on both the Improving blog and the AWS Database Blog.â€

About the Author

Ken Hu is a Senior Software Developer at Improving. He is a committer to the Apache TinkerPop project. Ken enjoys learning about different aspects of software development.

Source: Read More