For over a decade, GitHub has offered enterprise authentication using SAML (Security Assertion Markup Language), starting with our 2.0.0 release of GitHub Enterprise Server in November 2014. SAML single sign-on (SSO) allows enterprises to integrate their existing identity providers with a broad range of GitHub products, extend conditional access policies, and bring enterprise organization management to GitHub.

To ship this feature, we had to build and maintain support for the SAML 2.0 specification, which defines how to perform authentication and establish trust between an identity provider and our products, the service provider. This involves generating SAML metadata for identity providers, generating SAML authentication requests as part of the service provider–initiated SSO flow, and most importantly, processing and validating SAML responses from an identity provider in order to authenticate users.

These code paths are critical from a security perspective. Here’s why:

- Any bug in how authentication is established and validated between the service and identity providers can lead to a bypass of authentication or impersonation of other users.

- These areas of the codebase involve XML parsing and cryptography, and are dependent on complex specifications, such as the XML Signature, XML Encryption, and XML Schema standards.

- The attack surface of SAML code is very broad, so the data that is validated for authentication and passed through users’ (and potential attackers’) browsers could be manipulated.

This combination of security criticality, complexity, and attack surface puts the implementation of SAML at a higher level of risk than most of the code we build and maintain.

Background

When we launched SAML support in 2014, there were few libraries available for implementing it. After experimenting initially with ruby-saml, we decided to create our own implementation to better suit our needs.

Over the years since, we have continually invested in hardening these authentication flows, including working with security researchers both internally and through our Security Bug Bounty to identify and fix vulnerabilities impacting our implementation.

However, for each vulnerability addressed, there remained lingering concerns given the breadth and complexity of root causes we identified. This is why we decided to take a step back and rethink how we could move forward in a more sustainable and holistic manner to secure our implementation.

So, how do you build trust in a technology as complex and risky as SAML?

Last year, this is exactly the question our engineering team set out to answer. We took a hard look at our homegrown implementation and decided it was time for change. We spent time evaluating the previous bounties we’d faced and brainstormed new ideas on how to improve our SAML strategy. During this process, we identified several promising changes we could make to regain our confidence in SAML.

In this article, we’ll describe the four key steps we took to get there:

- Rethinking our library: Evaluating the ruby-saml library and auditing its implementation

- Validating the new library with A/B testing: Building a system where we could safely evaluate and observe changes to our SAML processing logic

- Schema validations and minimizing our attack surface: Reducing the complexity of input processing by tightening schema validation

- Limiting our vulnerability impact: Using multiple parsers to decrease risk

Rethinking our library

When we reviewed our internal implementation, we recognized the advantages of transitioning to a library with strong community support that we could contribute to alongside a broader set of developers.

After reviewing a number of ruby SAML libraries, we decided to focus again on utilizing the ruby-saml library maintained by Sixto Martín for a few reasons:

- This library is used by a number of critical SaaS products, including broad adoption through its usage in omniauth-saml.

- Recent bugs and vulnerabilities were being reported and fixed in the library, showing active maintenance and security response.

- These vulnerabilities and fixes were distributed through the GitHub Advisory Database and CVEs, and had updates pushed through Dependabot, which integrates well with our existing vulnerability management processes.

This support and automation is something we wouldn’t be able to benefit from with our own internal implementation.

But moving away from our internal implementation wasn’t a simple decision. We had grown familiar with it, and had invested significant time and effort into identifying and addressing vulnerabilities. We didn’t want to have to retread the same vulnerabilities and issues we had with our own code.

With that concern, we set out to see what work across our security and engineering teams we could do to gain more confidence in this new library before making a potential switch.

In collaboration with our bug bounty team and researchers, our product security team, and the GitHub Security Lab, we laid out a gauntlet of validation and testing activities. We spun up a number of security auditing activities, worked with our VIP bug bounty researchers (aka Hacktocats) who had expertise in this area (thanks @ahacker1) and researchers on the GitHub Security Lab team (thanks @p-) to perform in-depth code analysis and application security testing.

This work resulted in the identification of critical vulnerabilities in the ruby-saml library and highlighted areas for overall hardening that could be applied to the library to remove the possibility of classes of vulnerabilities in the code.

But is security testing and auditing enough to confidently move to this new library? Even with this focus on testing, assessment, and vulnerability remediation, we knew from experience that we couldn’t just rely on this point-in-time analysis.

The underlying code paths are just too complex to hang our hat on any amount of time-bound code review. With that decision, we shifted our focus toward engineering efforts to validate the new library, identify edge cases, and limit the attack surface of our SAML code.

Validating the new library with A/B testing

GitHub.com processes around one million SAML payloads per business day, making it the most widely used form of external authentication that we support. Because this code is the front door for so many enterprise customers, any changes require a high degree of scrutiny and testing.

In order to preserve the stability of our SAML processing code while evaluating ruby-saml, we needed an abstraction that would give us the safety margins to experiment and iterate quickly.

There are several solutions for this type of problem, but at GitHub, we use a tool we have open sourced called Scientist. At its core, Scientist is a library that allows you to execute an experiment and compare two pieces of code: a control and a candidate. The result of the comparison is recorded so that you can monitor and debug differences between the two sources.

The beauty of Scientist is it always honors the result of the control, and isolates failures in your candidate, freeing you to truly experiment with your code in a safe way. This is useful for tasks like query performance optimization—or in our case, gaining confidence in and validating a new library.

Applying Scientist to SAML

GitHub supports configuring SAML against both organizations and enterprises. Each of these configurations is handled by a separate controller that implements support for SAML metadata, initiation of SAML authentication requests, and SAML response validation.

For the sake of building confidence, our primary focus was the code responsible for handling SAML response validation, also known as the Assertion Consumer Service (ACS) URL. This is the endpoint that does the heavy lifting to process the SAML response coming from the identity provider, represented in the SAML sequence diagram below as “Validate SAML Response.” Most importantly, this is where most vulnerabilities occur.

In order to gain confidence in ruby-saml, we needed to validate that we could get the library to handle our existing traffic correctly.

To accomplish this, we applied Scientist experiments to the controller code responsible for consuming the SAML response and worked on the following three critical capabilities:

- Granular rollout gating: Scientist provides a percent-based control for enabling traffic on an experiment. Given the nature of this code path, we wanted an additional layer of feature flagging to ensure that we could send our own test accounts through the path before actual customer traffic

- Observability: GitHub has custom instrumentation for experiments, which sends metrics to Datadog. We leaned heavily on this for monitoring our progress, but also added supplemental logging to generate more granular validation data to help debug differences between libraries.

- Idempotency: There are pieces of state that are tracked during a SAML flow, such as tokens for CSRF, and we needed to ensure that our experiment did not modify them. Any changes must be clear of these code paths to prevent overwriting state.

When all was said and done, our experiment looked something like the following:

# gate the experiment by business, allowing us to run test account traffic through first

if business.feature_enabled?(:run_consume_experiment)

# auth_result is the result of `e.use` below

auth_result = science "consume_experiment" do |e|

# ensure that we isolate the raw response ahead of time, and scope the experiment to

# just the validation portion of response processing

e.use { consume_control_validation(raw_saml_response) }

e.try { consume_candidate_validation(raw_saml_response) }

# compare results and perform logging

e.compare { |control, candidate| compare_and_log_results(control, candidate) }

end

end

# deal with auth_result below...So, how did our experiments help us build confidence in ruby-saml?

For starters, we used them to identify configuration differences between implementations. This guided our integration with the library, ensuring it could handle traffic in a way that was behaviorally consistent.

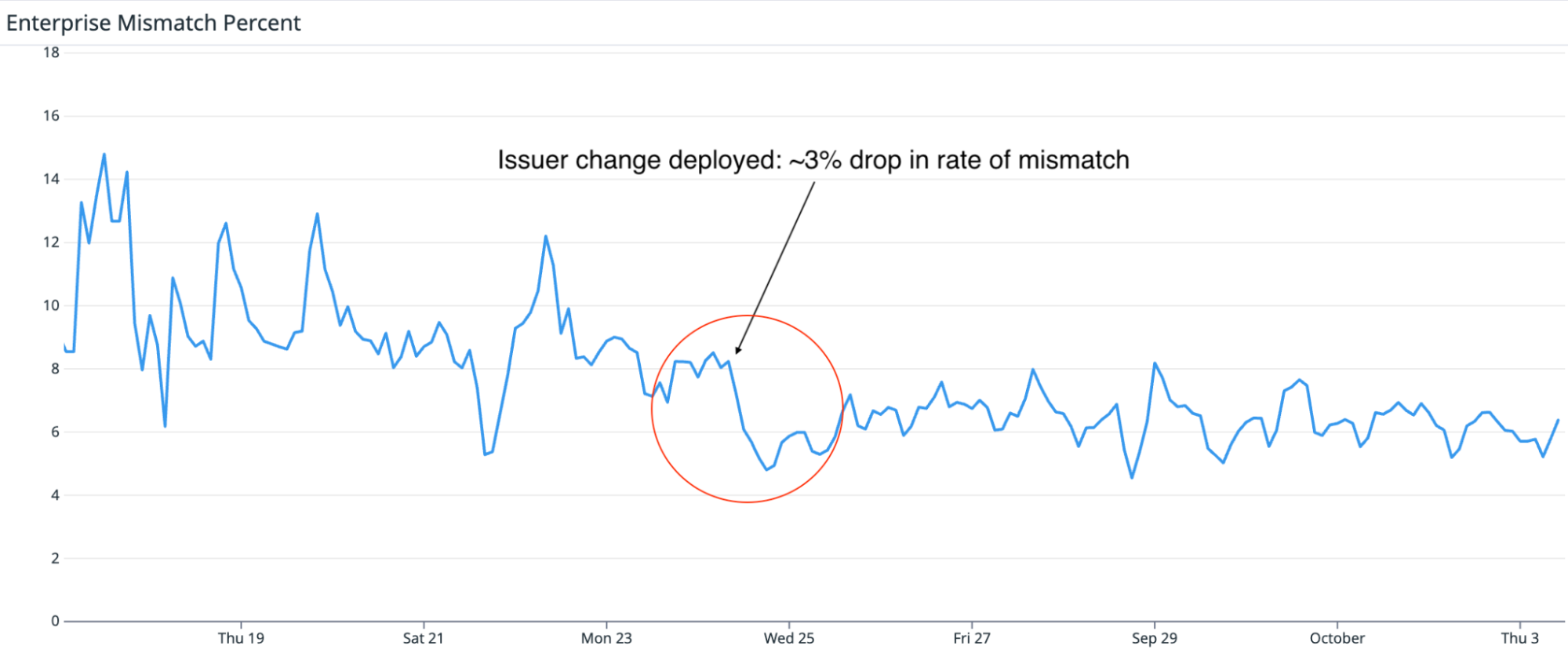

As an example, in September 2024 we noticed in our logs that approximately 3% of mismatches were caused by SAML issuer validation discrepancies. Searching the logs, we found that ruby-saml validated the issuer against an empty string. This helped us identify that some SAML configurations had an issuer set to an empty string, rather than null in the database.

Given that GitHub has not historically required an issuer for all SAML configurations, if the value is blank or unset, we skip issuer validation in our implementation. To handle this legacy invariant, we shipped a change that prevented configuring ruby-saml with blank or null issuer values, allowing the validation to be skipped in the library.

The impact of this change can be seen in graph below:

Once we set ruby-saml up correctly, our experiments allowed us to run all of our traffic through the library to observe how it would perform over an extended period of time. This was critical for building confidence that we had covered all edge cases. Most importantly, by identifying edge cases where the implementations handled certain inputs differently, we could investigate if any of these had security-relevant consequences.

By reviewing these exceptions, we were able to proactively identify incorrect behavior in either the new or old implementation. We also noticed during testing that ruby-saml rejected responses with multiple SAML assertions, while ours was more lenient.

While not completely wrong, we realized our implementation was trying to do too much. The information gained during this testing allowed us to safely augment our candidate code with new ideas and identify further areas of hardening like our next topic.

Schema validations and minimizing our attack surface

Before looking into stricter input validation, we first have to dive into what makes up the inputs we need to validate. Through our review of industry vulnerabilities, our implementation, and related research, we identified two critical factors that make parsing and validating this input particularly challenging:

- The relationship between enveloped XML signatures and the document structure

- The SAML schema flexibility

Enveloped XML Signatures

A key component of SAML is the XML signatures specification, which provides a way to sign and verify the integrity of SAML data. There are multiple ways to use XML signatures to sign data, but SAML relies primarily on enveloped XML signatures, where the signature itself is embedded within the element it covers.

Here’s an example of a <Response> element with an enveloped XML signature:

<Response ID="1234>

<Signature xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

<SignedInfo>

<CanonicalizationMethod Algorithm="http://www.w3.org/2001/10/xml-exc-c14n#"></CanonicalizationMethod>

<SignatureMethod Algorithm="http://www.w3.org/2001/04/xmldsig-more#rsa-sha256"></SignatureMethod>

<Reference URI="#1234">

<Transforms>

<Transform Algorithm="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#enveloped-signature"></Transform>

<Transform Algorithm="http://www.w3.org/2001/10/xml-exc-c14n#"></Transform>

</Transforms>

<DigestMethod Algorithm="http://www.w3.org/2001/04/xmlenc#sha256"></DigestMethod>

<DigestValue>...</DigestValue>

</Reference>

</SignedInfo>

<SignatureValue>...</SignatureValue>

<KeyInfo>

<X509Data>

<X509Certificate>...</X509Certificate>

</X509Data>

</KeyInfo>

</Signature>

</Response>In order to verify this signature, we performed some version of the following high-level process:

- Find the signature: Locate the

<Signature>element in the<Response>element. - Extract values: Get the

<SignatureValue>and<SignedInfo>from the<Signature>. - Extract reference and digest: From

<SignedInfo>, extract the<Reference>(a pointer to the signed part of the document—note the URI attribute and the associated ID attribute on<Response>) and<DigestValue>(a hashed version of<Response>, minus the<Signature>). - Verify the digest: Apply the transformation instructions in the signature to the

<Response>element and compare the results to the<DigestValue>. - Validate integrity: If the digest is valid, hash and encode

<SignedInfo>using another algorithm, then use the configured public key (exchanged during SAML set up) to verify it against the<SignatureValue>.

If we get through this list of steps and the signature is valid, we assume that the <Response> element has not been tampered with. The interesting part about this is that to process the signature that legitimizes the <Response> element’s contents, we had to parse the <Response> element’s contents!

Put another way, the integrity of the SAML data is tied to its document structure, but that same document structure plays a critical role in how it is validated. Herein lies the crux of many SAML validation vulnerabilities.

This troubling relationship between structure and integrity can be exploited, and has been many times. One of the more common classes of vulnerability is the XML signature wrapping attack, which involves tricking the library into trusting the wrong data.

SAML libraries typically deal with this by querying the document and rejecting unexpected or ambiguous input shapes. This strategy isn’t ideal because it still requires trusting the document before verifying its authenticity, so any small blunders can be targeted.

Lax SAML schema definitions

SAML responses must be valid against the SAML 2.0 XML schema definition (XSD). XSD files are used to define the structure of XML, creating a contract between the sender and receiver about the sequence of elements, data types, and attributes.

This is exactly what we would look for in creating a clear set of inputs that we can easily limit parsing and validation around! Unfortunately, the SAML schema is quite flexible in what it allows, providing many opportunities for a document structure that would never appear in typical SAML responses.

For example, take a look at the SAML response below and notice the <StatusDetail> element. <StatusDetail> is one example in the spec that allows arbitrary data of any type and namespace to be added to the document. Consequently, including the elements <Foo>, <Bar>, and <Baz> into <StatusDetail> below would be completely valid given the SAML 2.0 schema.

<Response xmlns="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:protocol" Version="2.0" ID="_" IssueInstant="1970-01-01T00:00:00.000Z">

<Status>

<StatusCode Value="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:status:Success"/>

<StatusDetail>

<Foo>

<Bar>

<Baz />

</Bar>

</Foo>

</StatusDetail>

</Status>

<Assertion xmlns="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:assertion" Version="2.0" ID="TEST" IssueInstant="1970-01-01T00:00:00.000Z">

<Issuer>issuer</Issuer>

<Signature xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

Omitted for Brevity...

</Signature>

<Subject>

<NameID>

user@example.net

</NameID>

</Subject>

</Assertion>

</Response>Knowing that the signature verification process is sensitive to the document structure, this is problematic. These schema possibilities leave gaps that your code must check.

Consider an implementation that does not correctly associate signatures with signed data, only validating the first signature it finds because it assumes that the signature should always be in the <Response> element (which encompasses the <Assertion> element), or in the <Assertion> element directly. This is where the signatures are located in the schema, after all.

To exploit this, replace the contents of our previous example with a piece of correctly signed SAML data from the identity provider (remember that the schema allows any type of data in <StatusDetail>). Since the library only cares about the first signature it finds, it never verifies the <Assertion> signature in the example below, allowing an attacker to modify its contents to gain system access.

<Response xmlns="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:protocol" Version="2.0" ID="_" IssueInstant="1970-01-01T00:00:00.000Z">

<Status>

<StatusCode Value="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:status:Success"/>

<StatusDetail>

<Response Version="2.0" ID="TEST" IssueInstant="1970-01-01T00:00:00.000Z">

<Signature xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

Omitted for Brevity...

</Signature>

</Response>

</StatusDetail>

</Status>

<Assertion xmlns="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:assertion" Version="2.0" ID="TEST" IssueInstant="1970-01-01T00:00:00.000Z">

<Issuer>issuer</Issuer>

<Signature xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

Omitted for Brevity...

</Signature>

<Subject>

<NameID>

attacker-controller@example.net

</NameID>

</Subject>

</Assertion>

</Response>There are so many different permutations of vulnerabilities like this that depend on the loose SAML schema, including many that we have protected against in our internal implementation.

Limiting the attack surface

While we can’t change how SAML works or the schema that defines it, what if we change the schema we validate it against? By making a stricter schema, we could enforce exactly the structure we expect to process, thereby reducing the likelihood of signature processing mistakes. Doing this would allow us to rule out bad data shapes before ever querying the document.

But in order to build a stricter schema, we first needed to confirm that the full SAML 2.0 schema wasn’t necessary. Our process began with bootstrapping: we gathered SAML responses from test accounts provided by our most widely integrated identity providers.

Starting small, we focused on Entra and Okta, which together accounted for nearly 85% of our SSO traffic volume. Using these responses, we crafted an initial schema based on real-world usage.

Next, we used Scientist to validate the schemas against our vast amount of production traffic. We first A/B tested with the very restrictive “bootstrapped” schema and gradually added back in the parts of the schema that we saw in anonymized traffic.

This allowed us to define a minimal schema that only contained the structures we saw in real-world requests. The same tooling we used for A/B testing allowed us to craft a minimal schema by iterating on the failures we saw across millions of requests.

How did the “strict” schema turn out based on our real-world validation from identity providers? Below are some of the key takeaways and schema restrictions we now enforce:

Ensure Signature elements are only where you expect them

We expect at most two elements to be signed: the Response, and the Assertion, but we know the schema is more lenient. For example, we don’t expect the SubjectConfirmationData or Advice elements to contain a signature, yet the following is a valid structure:

<samlp:Response ID="response-id" xmlns:samlp="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:protocol">

<saml:Assertion ID="signed-assertion-id">

<ds:Signature>

<ds:SignedInfo>

<ds:Reference URI="#signed-assertion-id" />

...

</ds:SignedInfo>

</ds:Signature>

<saml:Subject>

<saml:NameID>legitimate-user@example.com</saml:NameID>

<saml:SubjectConfirmation>

<saml:SubjectConfirmationData>

<ds:Signature>...</ds:Signature>

</saml:SubjectConfirmationData>

</saml:SubjectConfirmation>

</saml:Subject>

</saml:Assertion>These are ambiguous situations that we can prevent. By removing <any> type elements, we can prevent additional signatures from being added to the document, and reduce the risk of attacks targeting flaws in signature selection logic.

It’s safe to enforce a single assertion in your response

The SAML spec allows for an unbounded number of assertions:

<choice minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="unbounded">

<element ref="saml:Assertion"/>

<element ref="saml:EncryptedAssertion"/>

</choice>We expect exactly one assertion, and most SAML libraries account for this invariant by querying and rejecting documents with multiple assertions. By removing the minOccurs and maxOccurs attributes from the schema’s assertion choice, we can reject responses containing multiple assertions ahead of time.

This matters because multiple assertions in the document lead to structures that are vulnerable to XML signature wrapping attacks. Enforcing a single assertion removes structural ambiguity around the most important part of the document.

Remove additional elements and attributes that are unused in practice by your implementation

This is probably the least specific piece of advice, but important: Removing what you don’t support from the existing schema will reduce the risk of your application code handling that input incorrectly. For example, if you don’t support EncryptedAssertions, you should probably omit those definitions from your schema all together to prevent your code from touching data it doesn’t expect.

It is safe to reject document type definitions (DTDs)

While not strictly XSD related, we felt this was an important callout. DTDs are an older and more limited alternative to XSDs that add an unnecessary attack vector. Given that SAML 2.0 relies on schema definition files for validation, DTDs are both outdated and unnecessary, so we felt it best to disallow them altogether. In the wild, we never saw DTDs being used by identity providers.

The goal of a stricter SAML schema is to simplify working with SAML signatures and documents by removing ambiguity. By enforcing precise rules about where signatures should appear and their relationship to the data, validation becomes more straightforward and reliable.

While stricter schemas don’t eliminate all risks—since signature processing also depends on implementation—they significantly reduce the attack surface, enhancing overall security and minimizing the complex parsing we need to reason about for validation.

Limiting our vulnerability impact

At this point, we had made significant progress in addressing the risks associated with integrating ruby-saml and had restricted our critical inputs to a much smaller portion of the SAML schema.

By implementing safeguards, validating critical code paths, and taking a deliberate approach to testing, we mitigated many of the uncertainties inherent in adopting a new library and of SAML in general.

However, one fundamental truth remained: implementation vulnerabilities are inevitable, and we wanted to see what additional hardening we could apply to limit their impact.

Considering a compromise

Migrating to ruby-saml fully would mean embracing a more modern, actively maintained codebase that addresses known vulnerabilities. It would also position us for better long-term maintainability with broad community support: one of the primary motivators for this initiative.

However, replacing a core component like a SAML library isn’t without trade-offs. The risk of new vulnerabilities that weren’t surfaced during our work would always exist. With this in mind, we considered an alternative path: Instead of relying entirely on one library, why not use both?

We took this idea and ran with it by implementing a dual-parsing strategy and running both libraries independently and in parallel, requiring them to agree on validation before accepting a result. It might sound redundant and inefficient, but here’s why it worked to harden our implementation:

- Defense in depth: The two libraries parse SAML differently. Exploiting both would require two independent vulnerabilities that work in unison—a much taller order than compromising just one.

- Built-in feedback: When they disagree, we are notified. This gives us the opportunity to identify and investigate potential security critical edge cases. We can then feed stricter validation logic from one library back into the other.

- No pressure to rush: Our original library is battle-tested and hardened. Using both together allows us to leverage its reliability while adopting the benefits of ruby-saml. We can always revisit this decision as we learn more about this strategy and its performance over time.

With this approach, we recognize that keeping something that works—when paired with something new—can be more powerful than replacing it outright. Of course, there are still risks involved. But by having two parsers, we increase our exposure of implementation vulnerabilities in our XML parsing code: things like memory corruption or XML external entity vulnerabilities. We also increase the burden of having to maintain two libraries.

Despite this, we decided that this risk and time investment is worth the increased resilience to the complex validation logic that is the core to the historical and critical vulnerabilities we’ve seen.

Learn from our blueprint

While our original goal was to “just” move to a new SAML library, we ended up taking the opportunity to reduce the risk profile of our entire SAML implementation.

By investing in upfront code review, security testing, and A/B testing and validation, we’ve gained confidence in the implementation of this new library. We then decreased the complexity of these code paths by restricting our allowed schema to one that is minimized using real world data. Finally, we’ve limited the impact of a single vulnerability found in either library by combining the strengths of both ruby-saml and our internal implementation.

As this code continues to parse almost a million SAML responses per day, our robust logging and exception handling will provide us with the observability needed to adjust our strategy or identify new hardening opportunities.

This experience should provide any team with a great blueprint on how to approach other complex or dangerous parts of a codebase they may be tasked with maintaining or hardening—and a reminder that incremental, data-driven experiments and compromises can sometimes lead to unexpected outcomes.

Read more about GitHub Security Lab’s research into SAML vulnerabilities and how GitHub can help you secure your code.

The post Inside GitHub: How we hardened our SAML implementation appeared first on The GitHub Blog.

Source: Read MoreÂ